Gum Bacteria Causes Heart disease, Stroke, Alzheimer’s, and More?

We are all familiar with “lifestyle diseases” (Alzheimer’s, heart disease, stroke, diabetes, and others, all associated with age and behaviors.) In spite of numerous perspectives and significant research, what we know is that these conditions usually start causing symptoms later in life, and their prevalence is skyrocketing as we live longer. We also know that these conditions are connected to, and possibly caused by, inappropriate inflammation. Worldwide, 70 percent of all deaths are now attributed to these lifestyle diseases.

For over a decade we have realized that there are connections between gum disease or oral inflammation and lifestyle diseases but new research is suggesting that oral bacteria and specifically Porphymonas Gingivalis, a key gum disease bacteria, could be the cause of these pathologies. This is a shocking and concerning discovery. These bacteria have the ability to turn inflammation, the method our immune system uses to kill invaders, against us.

In disease after disease, we are finding that bacteria are covertly involved, invading organs, co-opting our immune systems to boost their own survival and slowly making bits of us break down. The implication is that we may eventually be able to defeat heart attacks or Alzheimer’s just by stopping these microbes.

DNA sequencing has revealed bacteria in places they were never supposed to be, manipulating inflammation in just the ways observed in these diseases.

Gum disease is, “the most prevalent disease of mankind”, says Maurizio Tonetti at the University of Hong Kong. In the US, 42 percent of those aged 30 or above have gum disease, but that rises to 60 percent in those 65 and older. It has been measured at 88 percent in Germany.

Strikingly, many of the afflictions of ageing – from rheumatoid arthritis to Parkinson’s – are more likely, more severe, or both, in people with gum disease. It is possible that some third thing goes wrong, leading to both gum disease and the other maladies. But there is increasing evidence that the relationship is direct: the bacteria behind gum disease help cause the others.

But how can the bacteria that cause gum disease play a role in all these conditions?

To answer that, we have to look at how they turn the immune system against us.

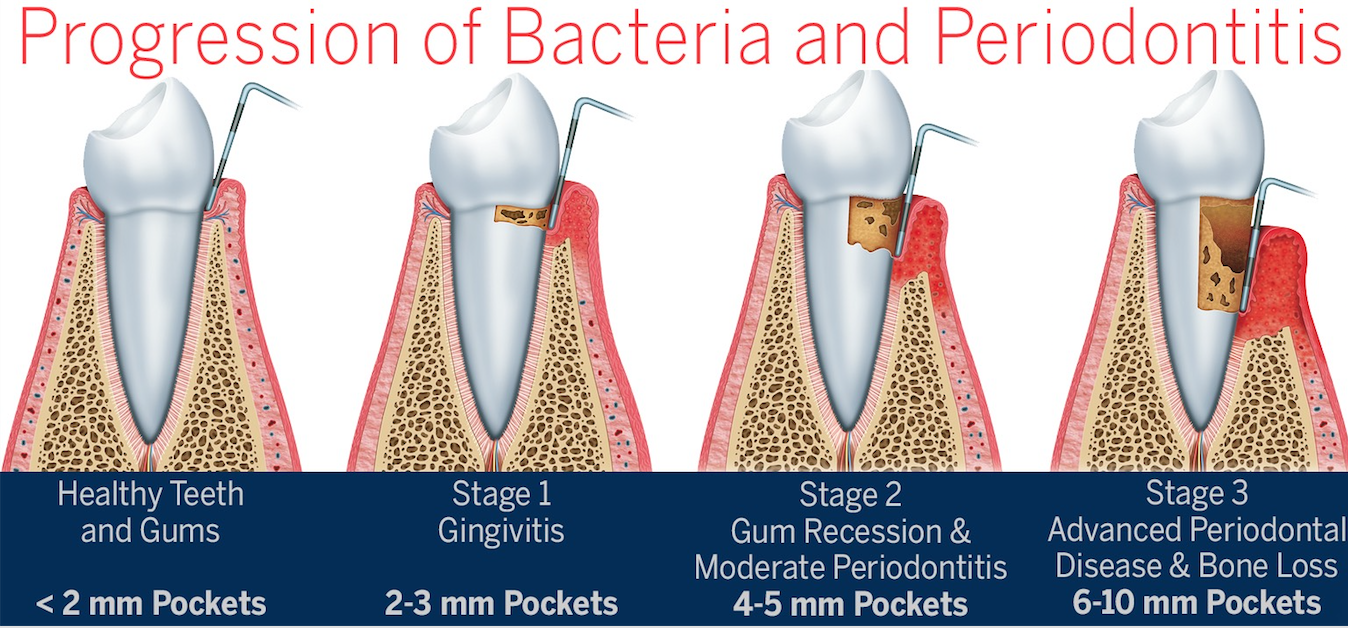

Reference Diagram:

When the plaque (bacteria filled white soft sticky debris on our teeth) builds up enough and is left long enough, it triggers acute inflammation: immune cells flood in and destroys both microbes and our own infected cells. At this early stage, you likely have bleeding puffy gums called gingivitis. Acute inflammation is an ideal defense mechanism to prevent infection and is a great time to realize there is a problem. If this goes on too long, an oxygen-poor pocket develops between gum and tooth. A handful of bacteria take advantage of this and multiply. One of them, Porphyromonas gingivatis, is especially insidious, disrupting the stable bacterial community and creating chronic inflammation. Chronic inflammation leads to attachment and bone loss around the teeth but even more concerning is the causal relationship of the lifestyle and ageing diseases that can and do take lives daily.

Eventually, the infected teeth can fall out but often not before P. gingivalis escapes into the bloodstream. There your immune system makes antibodies against it, which usually defend us from germs, but P. gingivalis antibodies seem to be more a mark of its passing than protection. People with these antibodies are actually more likely to die in the next decade than those with none, and more likely to get rheumatoid arthritis or have a heart attack or stroke.

This could be because, once in the blood, P. gingivalis changes its surface proteins so it can hide inside white blood cells of the immune system, says Genco. It also enters cells lining arteries. It remains dormant in these locations, occasionally waking to invade a new cell, but otherwise remaining hidden from antibiotics and immune defenses. However, even hunkered down within our cells, P. gingivalis continues to activate or block different immune signals, even changing a blood cell’s gene expression to make it migrate to other sites of inflammation, where the bacteria can hop out and feast again.

Gum disease bacteria can create a “drag” on our overall immune system. But P. gingivalis may act more directly too: the bacteria have been detected in inflamed tissue in the brain, aorta, heart, liver, spleen, kidneys, joints and pancreas in mice and, in many cases, humans.

If the bacterium Porphyromonas gingivalis is partly to blame for a wide range of inflammatory diseases such as Alzheimer’s and heart disease, why not just kill it?

Unfortunately, it is brilliant at dodging our defenses: lurking inside cells where antibodies can’t reach it, and often lying dormant, making it invisible to antibiotics, which mostly attack bacteria as they divide.

In studies by the company Cortexyme, antibiotics killed P. gingivalis in mice, but it rapidly became resistant. To limit resistance, instead of trying to kill the bacteria, it may be better to block its ability to cause disease. Cortexyme has a drug that does this by blocking gingipains. In mice, it reversed Alzheimer’s-like brain damage without driving resistance in P. gingivalis, and in a small trial in humans it improved inflammation and some measures of cognition. A large trial is now under way.

The strongest case against P. gingivalis is as a cause of Alzheimer’s disease. This constitutes more than two-thirds of all dementia, now the fifth largest cause of death worldwide. It was long blamed on the build-up of two brain proteins, amyloid and tau. But that hypothesis is crumbling: people with dementia may lack this build-up, while people with lots of the proteins may have no dementia – and most damningly, no treatments reducing either have improved symptoms.

Then, in January, teams at eight universities and the San Francisco company Cortexyme found a protein-digesting enzyme called gingipain, produced only by P. gingivalis, in 99 per cent of brain samples from people who died with Alzheimer’s, at levels corresponding to the severity of the condition. They also found the bacteria in spinal fluid. Giving mice the bacteria caused symptoms of Alzheimer’s, and blocking gingipains reversed the damage.

“A bacterial cause could explain the genetic risk for Alzheimer’s”

Moreover, half of the brain samples from people without Alzheimer’s also had gingipain and amyloid, but at lower levels. That is as you would expect if P. gingivalis causes Alzheimer’s, because damage can accumulate for 20 years before symptoms start. People who develop symptoms may be those who accumulate enough gingipain damage during their lifetimes, says Casey Lynch at Cortexyme.

- Gingivalis may literally break our hearts too. There is growing evidence for a causal link to atherosclerosis, or “hardening of the arteries”. Researchers have found P. gingivalis in the fatty deposits that line arterial walls and cause blood clots. When bits of clots clog blood vessels in hearts or brains, they cause heart attack and stroke.

The bacteria trigger the molecular changes in artery linings that are typical of atherosclerosis, says Genco. We have also found that P. gingivalis creates the lipoproteins thought to trigger atherosclerosis, causes it in pigs and affects arteries much like high fat diets. Lakshmyya Kesavalu at the University of Florida, who has cultured viable P. gingivalis from the atherosclerotic aortas of mice, calls the bacteria “causal”.

The American Heart Association agrees that gum disease is an “independent” risk factor for cardiovascular disease, but doesn’t call it causal. It argues that although treating gum disease improves hardened arteries, no studies have found that it reduces heart attacks or strokes. But, according to Steve Dominy at Cortexyme, that could be because, while gum treatment helps arteries by easing inflammatory load, it doesn’t eradicate the P. gingivalis already in the blood vessels. Clinical trials are needed to firm up the connection, but these are expensive and difficult – especially when the bacterial hypothesis is still in its early days.

The link is clearer for type 2 diabetes, in which people lose sensitivity to insulin and eventually can’t make enough to control blood sugar. It is currently a pandemic, blamed on the usual lifestyle suspects.

Diabetes worsens gum disease, because high blood sugar levels hurt immune cells. But gum disease also worsens diabetes, and treating it helps as much as adding a second drug to the regimen taken by someone with the condition, according to the American Academy of Periodontology. Treatment is now recommended by diabetes associations, yet none of them list gum disease as a risk factor. As with other conditions, there is evidence that P. gingivalis isn’t promoting diabetes just by adding to the body’s inflammatory load, but may also be acting directly in the liver and pancreas to cut insulin sensitivity.

“It is very hard to prove causation in a complex disease,” says Genco. We know that mice given a mouthful of P. gingivalis get gum disease – and diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, atherosclerosis, fatty liver disease and Alzheimer’s-like symptoms. We know that, in humans, gum disease makes the other diseases more likely, and that P. ingivalis lurks in the affected tissues and makes the precise cellular changes typical of these conditions.

People who drink more alcohol tend to have more P. gingivalis and are more susceptible to gum disease. Tobacco smoke helps the bacteria to invade gum cells. Exercise, the only known way to lower your risk of Alzheimer’s, improves gum disease by damping inflammation and ending P. gingivalis’s feast.

Then there is diet. Douglas Kell at the University of Manchester, UK, believes our blood contains many dormant bacteria, needing only a dose of free iron to awaken and cause disease. That could be why eating too much red meat and sugar or too little fruit and veg lead to these diseases: all increase your blood iron.

“It’s perhaps too easy to mock the notion that flossing your teeth may contribute to good brain health,” says Margaret Gatz at the University of Southern California. And that may be part of why this idea hasn’t yet taken off in mainstream medicine. “There is a history of dental and medical doctors working apart and not cooperating,” says Thomas Kocher at the University of Greifswald, Germany.

But it also reflects the long-held belief that heart attacks and the other conditions are primarily the result of bad lifestyle, not bacteria. Such underlying paradigms in science can take decades to change. That happened when bacteria, not stress and stomach acid, were shown to cause stomach ulcers. After decades pursuing these explanations, many medical experts are reluctant to admit that amyloid may not cause Alzheimer’s and high cholesterol may not lead to heart disease.

With the world’s population ageing, we don’t have decades before these diseases become a health crisis severe enough to break health systems and societies. We need a new paradigm. That means facing the possibility that it may all be down to germs, after all.

With the world’s population ageing, we don’t have decades before these diseases become a health crisis severe enough to break health systems and societies. We need a new paradigm. That means facing the possibility that it may all be down to germs, after all.

Germ Theory

Simply stated, there is growing evidence that demonstrates that the bacteria in our mouths cause many common diseases.

Rheumatoid arthritis

- gingivalis is present in the joints of people who get this condition before symptoms appear and is the only bacterium known to make a chemical involved in the disease.

Parkinson’s disease

- gingivalis and its protein-munching enzymes, gingipains, are found in the blood of people with Parkinson’s disease, and promote the inflammation and abnormal clotting seen in the condition.

Kidney disease

Gum disease is associated with chronic kidney disease and gum treatment seems to help the kidneys.

Fatty liver disease

There is far more P. gingivalis in affected livers than in healthy ones, and it worsens the disease in mice. Treating the gums helps.

Cancer

The bacteria has been found in early-stage cancers of the mouth, oesophagus, stomach and pancreas, and changes cell functions in ways typical of these cancers.

Macular degeneration

Injecting the bacteria into the retina seems to damage eyesight by producing age-related macular degeneration in mouse studies.

Preterm birth

Gum disease, caused by P. gingivalis, has been established as a risk for premature birth.

What should we do?

An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.

- See your dentist– gum disease is usually painless until it is severe. If your gums bleed when you brush or floss it can be considered a warning sign that your tissues are under attack from bacteria in the mouth.

- After going to your dentist: Your dentist will clinically examine your gums, take x-rays to see the bone, measure the gum pockets around the teeth and give you a diagnosis of gum health. If you do not have gum disease, commit to a plan of regular maintenance: get a thorough cleaning at your dental office every 6 months, floss daily (See my article entitled WTF: What the Floss archived in the locals guide https://ashland.oregon.localsguide.com/wtf-what-the-floss ), and Brush for a minimum of 2 minutes 2 times per day.

- If you have periodontal disease: Take it seriously. A minimum of 3-4 dental visits per year are necessary to manage the inflammation and bacterial load. Utilize a water flosser in deeper pockets, and visit with your dentist for strategies to suit your specific needs. Reducing chronic inflammation will limit the risk of increased bacteria entering the blood stream.

- Remember the best solution for preventing these bacteria from causing systemic disease is to limit its presence. Early habits that reduce bacterial load will pay dividends over a life time. This means developing a habit of good hygiene (yes that means flossing) will pay dividends over a lifetime. Share that message with your friends and loved ones.

If you have further questions please take a look at the New Scientist article or ask your dentist.

Reference: New Scientist 7 Aug 2019