Slowing Water, Protecting Land: Jenny Kuehnle and Alicia Vlass of Ahimsa Gardens

Water is one of the most precious resources on our planet, yet many modern water management practices have dramatically altered its natural cycle, contributing to increased drought, desertification, and fire risks. Jenny Kuehnle and Alicia Vlass, of Ahimsa Gardens LLC, and some of their coworkers are on a mission to change that through the practice of “slow water.” By designing rain gardens and implementing water retention strategies, Ahimsa Gardens is working in Southern Oregon to create healthier soils, resilient plant life, and fire-resistant landscapes. In this interview, Jenny and Alicia share insights into the significance of slow water, the ecological impact of rain gardens, and simple ways that many people can contribute to restoring balance to our environment.

Hi Jenny and Alicia, thank you very much for taking the time to speak with us today! To begin with please tell us about your business Ahimsa Gardens and the work you are doing here in Southern Oregon.

Jenny: Hi Shields, I started Ahimsa Gardens in 2016 with a small crew. We have grown a lot, especially in the last 5 years, due to the incredible crew that we have. We have 16 employees including master stone masons, skilled carpenters and welders, irrigation technicians, conscientious maintenance workers, an in house designer, and an office manager who holds everything together. I am truly grateful for all of my co-workers and enjoy watching everyone’s interests and expertise expand in the work setting. My co-worker Alicia Vlass, who joined Ahimsa in 2022 is here with me for this interview, as the topics that we will be discussing are passions of hers as well.

Alicia, please tell us about the concept of “slow water,” and why is it crucial for a healthy and balanced ecosystem?

Alicia: Water is dynamic, moving through earth’s major water reservoirs. Oceans hold about 97% of the earth’s water; ice and snow are the second largest reservoir; then groundwater and surface water are the third largest reservoir. The natural flow of water moves through high altitude grasslands and forests, wetlands and floodplains. The groundwater and surface water are two parts of the water cycle that we can engage with and learn from. Slow water is a key concept in a healthy water cycle.

Conservation biologist Brock Dolman explains slow water through the phrase ‘slow it, spread it, sink it, store it and share it’ – all with the intention of maintaining clean, sustainable water patterns and flows. Groundwater is stored below the earth’s surface, residing within porous rocks and sediments and filling space in between soil particles. Lakes, rivers and wetlands are identified as surface water. The phrase ‘slow it, sink it, spread it’ is highly applicable to these types of water, and we can influence the quantities of water storage in many different ways; rain gardens and bioswales are two tangible examples of slowing and sinking water on an urban landscape scale.

To understand slow water, we must also recognize ‘fast water.’ In urban environments, humans typically divert water into quick, narrow impermeable pathways which contrasts wildly with water’s true nature. The fast speed at which we typically move water through human developments contributes to soil dehydration and water cycle disruptions, leading to climate catastrophe.

Our disconnect from water has created fragmented ecosystems that are struggling deeply.

Water is a vital resource for all life on earth. Changing water’s course and pace directly affects all beings, ecosystems and climate patterns.

Not only does ‘slow water’ help with soil hydration but it also helps with fire resilience. Please say more.

Jenny: Humans have drastically impacted and altered the land we live on, through urbanization, altering natural drainage pathways, grading and excavation, deforestation and vegetation reduction, paving and creating impervious surfaces, dam construction, and pollution. Reduced soil coverage by vegetation leads to erosion, destruction of soils, and ultimately, desertification of once lush ecosystems. The impermeable surfaces of urbanization inhibit ground water recharge. Many modern agricultural practices utilize irrigation practices that deplete groundwater reserves. Slow water practices, on the other hand, support soil hydration, healthy soils, and an intact water cycle. Larger quantities of water stored in groundwater reserves support diverse plant and soil life, keeping plant life green, hydrated, and less flammable. Thriving plants and living soils directly correlate to a more fire resilient landscape.

Beavers play a significant role in creating a fire resilient landscape, as their dams slow and spread out water into the soils like a damp sponge. This encourages groundwater recharge which directly influences how prone a landscape is to wildfire. Hydrated areas with healthy beaver activity are a safe refuge for many species during wildfires.

Can you explain the historical impact of human activity on soil hydration and desertification?

Alicia: For a simple example of human activity influencing the water cycle and soil hydration we can turn to green and grey infrastructure.

Grey infrastructure includes the human created aspects of a water system like pipes, spring boxes, wells or dams. Green infrastructure refers to the natural aspects of our water systems such as forests, wetlands, rivers, and riparian zones. In general, implementing green infrastructure, and finding nature based solutions can be more cost effective than grey infrastructure, and is supportive to the water cycle.

Soil hydration is supported by slow water practices. On the contrary, desertification, by removing water from land as quickly as possible, is a land degradation process that minimizes soil biodiversity and water capacity to the point of desert-like conditions. There are an immense number of causes, human activity being a significant contributor. How we relate to water, soil and all living systems is crucial. To lean on the wise words of Indigenous scientist Robin Wall Kimmerer, all flourishing is mutual.

How do rain gardens work, and what are their key benefits?

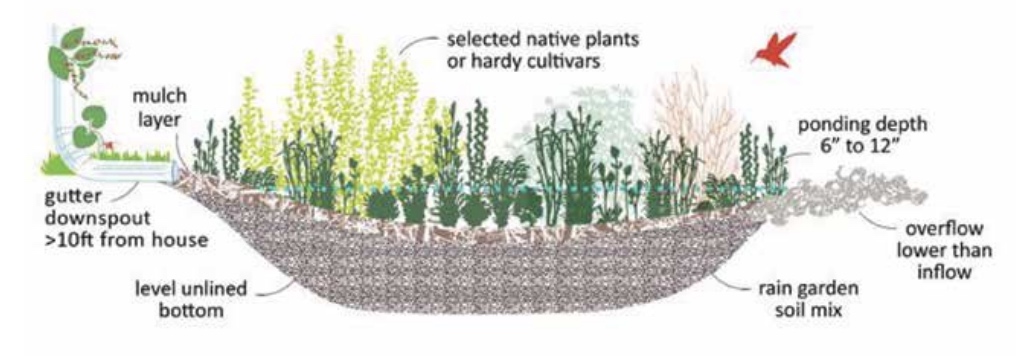

Alicia: Rain gardens are a great way to slow down water and recharge underground aquifers in an urban setting. Rain gardens are a depression in the land that are created to collect, slow, spread and sink storm water runoff into the soil. They are planted with a variety of plants, which filter pollutants through a process called phytoremediation. Rain gardens and bioswales reduce flooding and support the ground water by allowing the water to percolate directly into the soil. By building healthy soils and healthy plant communities, rain gardens also reduce flooding in local streams. Rain gardens filter sediment and pollutants through nutrient cycling or by sequestering pollutants in the soil or in the plants themselves. Rain gardens cleanse, detain, and reduce runoff by allowing water to seep into surrounding soil. Rain gardens are a practical example of “slow it, spread it, sink it” by diverting water back into the soil to help feed the groundwater to build soil hydration rather than into storm drains that quickly funnel water down impermeable surfaces.

There are other ecological benefits from rain gardens as well. Filtering runoff and slowing the influx of water into our streams and rivers during a storm event is crucial for salmon and other aquatic species.

What are some common misconceptions about water management and fire prevention?

Jenny: Healthy soils are living soils. Living soils are more fire resistant than dehydrated, dead soils. Healthy soils are hydrated, hold moisture, have plant roots, microbial and fungal life. Healthy soils have organic matter that continuously breaks down to feed the soil from above. Beneficial soil microbes and beneficial fungal communities live in healthy soil, break down nutrients to make them available to the plants, and even communicate with neighboring plants via mycelium threads. In order for this biology to thrive, soil needs to hold moisture and it to be protected from ultraviolet light. UV rays will damage exposed soil by killing all of the microbial life in the top few millimeters. For soil to thrive, soil temperatures must be kept cool and the soil must be covered with organic matter or plants to protect it from UV light.

Understandably, people are very concerned about wildfires in the Rogue Valley and in the West. It is sensible to create defensible space, clear out some underbrush, keep gutters clean, keep a 3-5 foot buffer clear around the perimeter of the house, remove indoor floor to ceiling fabric curtains, replace wood shake shingles with metal roofs, keep landscape plants trimmed to prevent ladder fuels, keep dry dead twigs pruned out of your landscape plants, etc. However, I notice that sometimes these suggestions are taken to the extreme. I have seen homeowners rake up all of their mulch from the entire yard and leave bare exposed soil. This leads to soil compaction, water runoff, exposes soil to UV rays, dehydrates and heats the soil. I have also seen homeowners remove the majority of their shrubs and trees, mulch the entire yard with rock, and reduce any remaining plants to tiny specimens of what they naturally want to be.

These extreme modifications further dehydrate the soils, disrupt the water cycle, cause runoff, compaction, and soil degradation, increasing the ‘urban heat island effect’ (the fact that temperatures in urban areas are higher than temperatures in surrounding natural areas). Soil needs plants and roots to thrive. Soil needs to be protected with organic matter and plants to retain moisture. The transpiration from plants in our landscapes helps seed the rain clouds, keeps the earth cooler and helps to keep the water cycle intact. We need a balanced approach to firewise landscapes that includes natural mulches that breakdown and feed the soil, and includes native fire adapted plants that our native insects and birds depend on.

Rain gardens and bioswales, into which we can divert our storm water from impervious surfaces, like rooftops, parking lots, and streets, mimic the work of beavers in natural settings. The hydrated land and plants around a beaver dam act as a firebreak during forest fires. The moist spongy soils created near beaver dams and the hydrated plants are more fire resistant than the surrounding terrain. We can easily create and maintain similar rain garden ‘firebreaks’ in our urban settings.

Alicia, could you please speak to the role that beavers have historically played in maintaining healthy ecosystems—and what can we learn from them when designing landscapes today?

Alicia: Beavers are a keystone species and the ultimate slow water teachers. As we face climate change, we have the opportunity to turn to the natural world, to observe and listen deeply to all beings. To implement slow water practices in our local community, we can orient to the teaching of the beaver.

Beavers help mitigate floods, prevent drought and wildfire, improve water quality, sequester carbon and create diverse habitats. The history of the beaver is crucial to understanding colonization, industrialization, genocide and ecocide. All of these have affected the history of the greatest slow water engineers on earth.

Initially fur trapping devastated the beaver population. Prior to the 17th century there were between 100-400 million beavers in North America. Beavers nearly went extinct by the mid 19th century. Currently, after fur trapping declined and protective measures were taken, beaver populations are on the rise. There are now an estimated 10-15 million beavers in North America. There are active beaver reintroduction programs, and in areas where that is not possible we can do the work of beavers through rain gardens and slow water practices.

The innate intelligence of beavers is shown in the dam complexes, bank burrows and canals that affect watersheds in a diverse way. Beavers create dams within creeks and rivers, slowing and spreading the general flow. In times of higher water concentrations the beaver dams reduce the intensity of floods. The slowing of water promotes riparian vegetation growth and erosion control. Beaver dams support not just the beavers but also other species. Native birds build their nests on top of beaver dams. In times of wildfire, dams and waterways that are tended by beavers are an oasis to many species.

With correct methods and a clear understanding of the local ecosystem it is possible to reintroduce beavers in an urban environment. Ahimsa Gardens has partnered with The Freshwater Trust on several restoration projects with the hopes of bringing back the beaver, and a beaver was spotted last year at one of these sites!

What are some practical ways individuals and communities can incorporate slow water principles into their landscapes?

Jenny: Building soil health, installing rainwater catchment and/or grey water irrigation systems, and rain gardens are all great ways to incorporate slow water principles into your landscaping. Rain gardens are a relatively low cost solution to manage stormwater, and can be installed quite easily and with relatively few resources. Rain gardens are beautiful, low maintenance, unique to each landscape, and offer a huge range of ecological benefits. If a client is interested in rainwater collection for irrigation, but for budget reasons needs to install the system in phases, a rain garden can be a great starting point and can later be integrated into a full rainwater collection system. In the presence of a rainwater collection system, a rain garden will serve as a place for overflow to go after rain tanks have filled for the season.

Can you walk us through the process of designing and installing a rain garden?

Jenny: Absolutely. First of all, it is important to locate the rain garden in an area where the water can easily be diverted from the storm gutters or impermeable surfaces with gravity. Obviously all sites are not suitable for this. It is also important that the rain garden is located downhill from the built structures, so that we do not compromise the stability of structures by adding moisture to the soil. There needs to be a safe place for overflow from the rain garden to flow in an extreme storm event. Once the location for the rain garden is chosen, we calculate how much rain will be diverted from the impermeable surfaces into the rain garden, and the volume of water that the rain garden will need to be able to accommodate. That and the soil composition (clay soils drain slower) help to determine the depth and size of the rain garden. We then plant the rain garden with native species that can handle the water fluctuations and that help to filter pollutants from the water.

What native plants are best suited for rain gardens, and how do they contribute to ecological balance?

Jenny: There are many options for plants to go in the rain garden. Depending on the site you will need to determine the sun/shade requirements and deer resistance of the plants. Different plants are planted at different levels in the rain garden. I’ve included here a small list, only things that are native to North America and to the West. The plants have different benefits; including filtering impurities from the water, providing nectar and pollen for native pollinators, they can handle being submerged in water for short periods of time.

Raingarden bottom:

Carex densa – dense sedge

Carex obnupta – slough sedge

Juncus patens – California grey rush

Ranunculus occidentalis – Western buttercup

Saxifraga oregana – Oregon saxifrage

Raingarden side slopes:

Bromus carinatus – California Brome

Deschampsia cespitosa – Tufted Hairgrass

Elymus glaucus – Blue Wildrye

Festuca occidentalis – Western Fescue Grass

Raingarden top layer:

Cornus stolonifera – Redosier Dogwood

Crataegus douglasii – Black Hawthorne

Lonicera involucrata – Black Twinberry

Oemleria cerasiformis – Indian Plum

Physocarpus capitatus – Ninebark

Rosa nutkana – Nootka Rose

Rosa pisocarpa – Peafruit Rose

Salix scouleriana – Scouler Willow

Salix sitchensis – Sitka Willow

Sambucus caerulea – Blue Elderberry

Spiraea douglasii – Douglas’ Spiraea

Symphoricarpos albus – Snowberry

What is your vision for the future of water management, and how can people get involved in supporting this movement?

There are so many things that people can do to manage water better. We need to continuously educate ourselves and make conscientious lifestyle changes in our homes, in our yards, our towns, and on a large scale too. We have put together a list of resources from which a lot of the information in this article came, and that people can use to delve more into the inspiring topic of slow water management.

Books/Authors:

Water Always Wins Erica Gies

Beaverland Leila Philip

Braiding Sweetgrass Robing Wall Kimmerer

Podcasts:

Climate Water Project podcast

Slowing our waters: Erica Gies

Beavers, biology, and slow water: Brock Dolman

Green and Grey Infrastructure: Angelina Cook

Sites/Organizations:

Occidental Arts and Ecology Center

The Beaver Institute

The Environmental Literacy Council

https://environmentgo.com/human-causes-of-desertification/

Jenny and Alicia, thank you and your team for doing the great work you do!

Thank you very much Shields for providing a platform to start these discussions. And thank you to all of the readers who read this article! Special thanks to Alicia for her passion and effort to get this information out there. During these times, when the economy seems shaky and there are so many unknowns and fears, it is vital that we take action in our own homes and communities. There is so much that we can do to restore the water cycle, protect our landscapes, create habitat for native creatures, and create a more sustainable future. Ahimsa Gardens is here to learn, share, serve, and help lead the way.

Learn More:

Ahimsa Gardens

541-324-8461

Website: ahimsagardens.com

Instagram: ahimsa_gardens