Cone Beam Computed Tomography

It has been several months since I wrote about anything clinical, so this month I would like to help us better understand the importance of accurate imaging in the treatment planning and surgical phases of implant dentistry. To do this I will share two cases that illustrate different aspects of treatment that the dental implantologist should be concerned with.

Many people hear about the benefits of implant dentistry and how great it would be to have “teeth” again. Media marketing touts how easy it is to get dental implants. Sales people promote how quick and simple the process is. And while there are a few “simple” cases out there, most require more thought with respect to engineering a long-lasting, trouble-free tooth replacement.

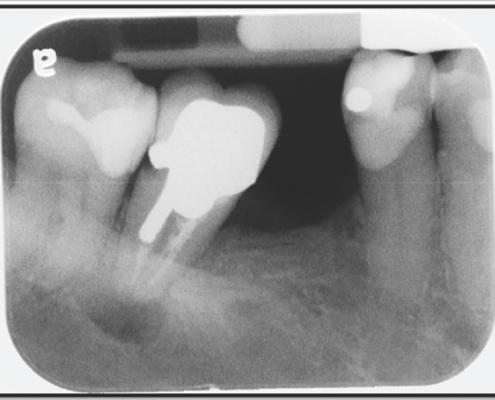

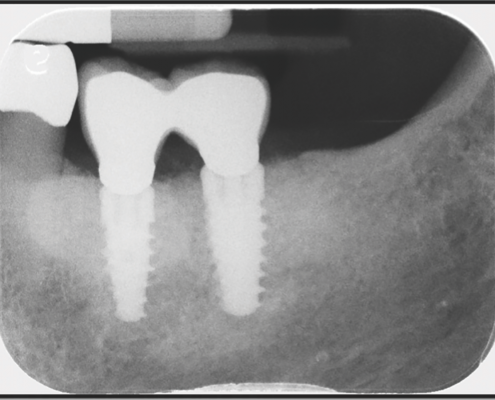

For example, the radiograph below features a patient with a missing tooth and another tooth that is failing (note the large black round area at the root tip of the tooth in the middle).

The hopeless molar was removed and the area was allowed to heal. After an appropriate healing time, a new image was taken of the area. However, it was a different type of image. The above image is a standard 2-D periapical radiograph, which allows us to see the region in two dimensions. The images below are derived from a Cone Beam Computed Tomography (CBCT) scan. They allow us to visualize the area in three dimensions and to see how much bone is really available for implant placement.

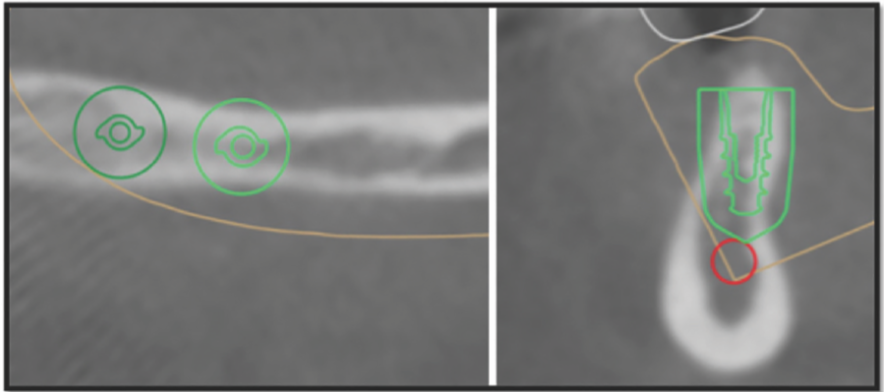

Looking down on jawbone Cross-sectional view of jawbone

On the left we are looking straight down on the bony ridge of the lower jaw. The larger round green circle is the safety zone and the green oblong shape inside the circle is the profile of the implant. On the right, we are looking at a cross-section of the bony ridge. Both views show how wide the bone is from different perspectives. The red circle in the right hand image is the outline of a nerve, the larger green outline is the safety zone, and the serrated green outline inside is the profile of the implant. Please note, in the right hand image we can see that the implant diameter is equal to the width of the bone at the topmost point. This means that there would be no bone around the implant here. So, the obvious conclusion is that that ridge of bone is too thin for successful implant placement.

Unfortunately, there are dentists who place implants “flaplessly” meaning that they do not expose the bone during surgery to evaluate it and they have not used CBCT imaging during their treatment planning. In essence, they are flying blind and hoping that the implant ends up in bone. Other dentists may use a CBCT image and decide that a narrow diameter implant will work, only to have the implants fail several years later because the implants are too small to support the chewing load placed upon them.

A better approach is to evaluate the available bone pre-operatively and, if the bone is insufficient to support properly sized implants, augment the bony ridge with a bone graft. This is exactly what was done in this case. The images below show the bony ridge before and after augmentation (if you look closely at the after images, you can see the original contour of the bone and where the bone grafting has increased the width of the bone).

A larger diameter implant is desired because the molar area is a high force area for chewing. The larger diameter is analogous to a snowshoe, whereas a smaller diameter would be analogous to the heel of a high-heeled shoe. While the same amount of chewing force may be applied to the implants, the larger diameter disperses that force over a greater surface area while the smaller one concentrates the force, which typically overloads the bone and results in bone loss.

So, one great reason to use a three dimensional image is to evaluate bone volume and determine whether or not bone grafting would be beneficial. Another reason is to help avoid important anatomical structures. One of the most notable structures the implant dentist should avoid contact with is the inferior alveolar nerve. This nerve enters a tunnel in the lower jaw on the tongue side behind the back molars, runs through the jawbone, and exits the bone in the premolar area on the lip side. The nerve supplies the teeth it travels underneath with sensation and it provides sensation to the lip, cheek, and muscles on the same side.

Before CBCT imaging, inferior alveolar nerve injury was something that occasionally happened. Using 2-D imaging, dental implant surgeons would do their best, but because they could not see everything in 3-D, nerves were occasionally damaged. Even with CBCT imaging inferior alveolar nerves were still being damaged during the surgical placement of dental implants because it can be difficult to control an implant drill without a guide. The current, state-of-the-art approach to dental implant surgery involves the use of CBCT images, dental implant planning software, and “fully guided” surgical guides that are made from this software.

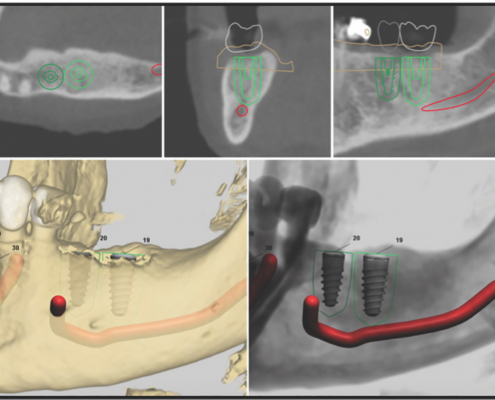

Here is a case that I completed using a fully guided technique. The patient only had her lower front six teeth and wanted to be able to chew food better. After discussing several different treatment plans, the patient decided to have 4 implants placed, 2 on each side, to provide her with greater ability to chew food.

Implant planning software takes the raw CBCT image files and places them in a viewing software that allows the dentist to virtually place the implants with the benefit of being able to view the spatial relationships of the implants to other important anatomical features. The image on the lower right of the above collage shows the inferior alveolar nerve in red and the positioning of the implants. And while the above image is a static 2-D image, the viewing software allows the dentist to rotate the image and view the spatial relationships from any angle.

Once the implants are positioned in the planning software, a surgical guide can be created that will enable the implant surgeon to place the implants in the exact position that has been planned, taking much of the guesswork and stress out of the process of implant placement in challenging places. It should be noted that a guide is only as good as the process used to make it and that human error can still enter the process. For this reason it remains vitally important that the implant dentist always exercise care, skill, and good judgment during implant surgery.

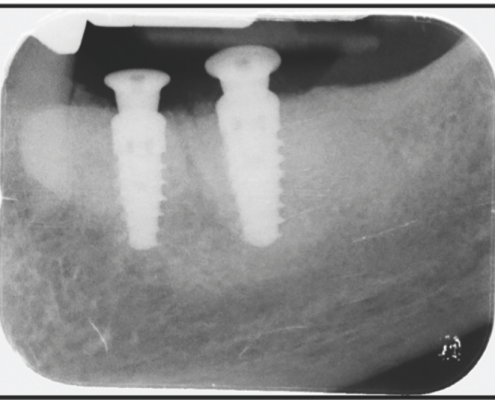

The images below show the successful placement of two dental implants without impingement on the inferior alveolar nerve and the placement of the crowns on the implants, completing the restorative phase of treatment and enabling the patient to function better and enjoy eating.

As a consumer, what should one be thinking about as one considers dental implants? One of the most important aspects is that dental implant placement should be considered a service and not a product. A product is the same no matter where it is purchased. For example, a Sony television can be purchased at Wal-Mart, Best Buy, or online from Amazon. The television will be the same because it is a product. On the other hand, a haircut is a service. And while the scissors and shampoo and styling gel used in the process may be the same at a variety of establishments, the care, skill, and judgment of the stylist will vary. The same holds true with implant dentistry – the implants, the drills, and the crowns may all be the same, but the care, skill, and judgment involved may vary widely among providers.

I hope this has been helpful information. If you have questions about implant dentistry, please contact your dental office and talk with your dentist. If you do not currently have a dentist, please call our office at 541-482-7771